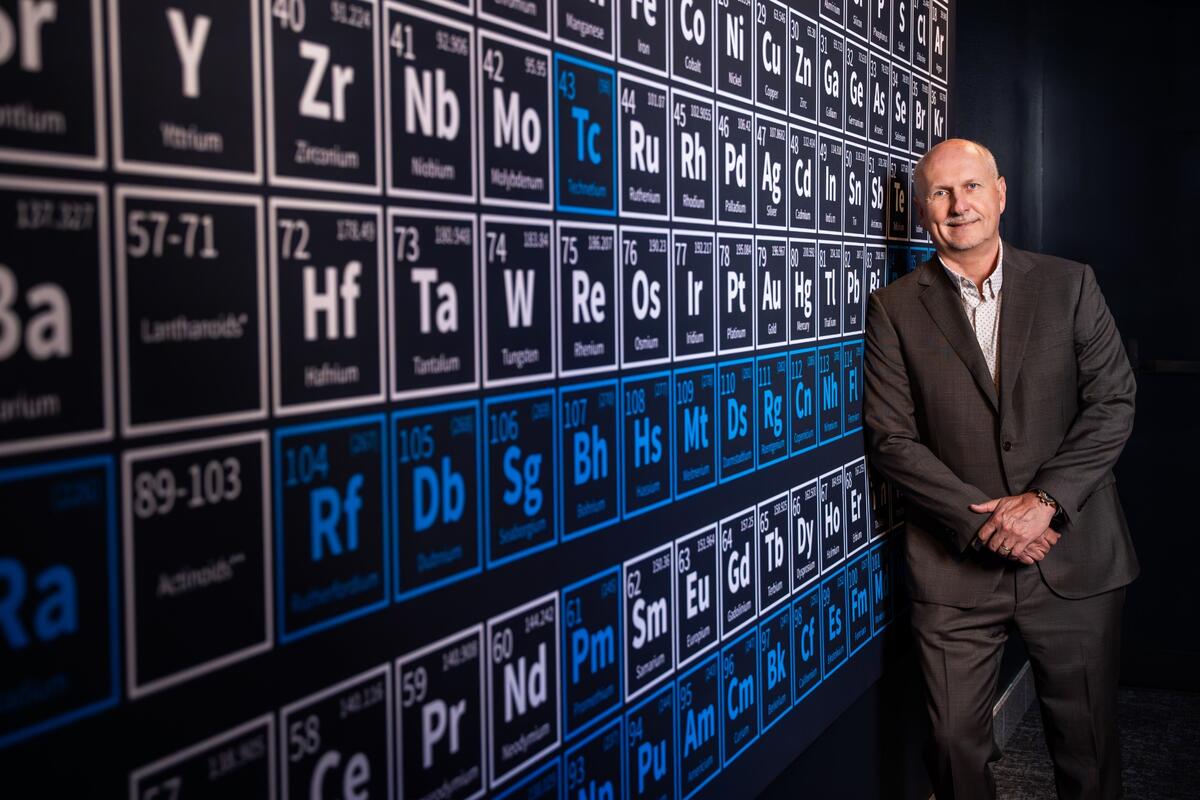

Scott Wade

For most undergraduate students, college is the penultimate stop on the way to full-blown adulthood — the place to discover or solidify professional passions while at the same time enjoying the kind of autonomous freedom that eludes the vast majority of the workforce.

Sometimes, though, the professional passion finds the student. And on rare occasions, that student — even while still working toward their degree — unwittingly gets thrust into a career that ends up lasting a lifetime.

This is where Scott Wade raises his hand and says, “Yep — that was me!”

“When I started at UNLV, I would have never guessed this is where my life and career would take me,” Wade says. “But it certainly worked out.”

About that career: It spanned more than three decades in the field of environmental sciences — the vast majority of which was spent working in various capacities for the U.S. government.

Those capacities ranged from the very bottom of the totem pole (cleaning glassware and grinding frozen fish samples for analysis in the Environmental Protectoratory, which Wade did while still a UNLV student) to the very top (serving as the senior advisor for environmental management for the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration, a position from which Wade retired in 2022).

It all started in 1981, when the Las Vegas native landed a part-time on-campus job in conjunction with the Environmental Protection Agency’s stay-in-school program, an initiative intended to attract students to the federal organization via jobs ranging from clerical to technical.

“I heard about it from a friend who also was a UNLV student and worked part time at the EPA,” says Wade, the 2025 College of Sciences Alumnus of the Year. “Given my interest in science, she thought the job would be a good fit — as it turned out, she was right.”

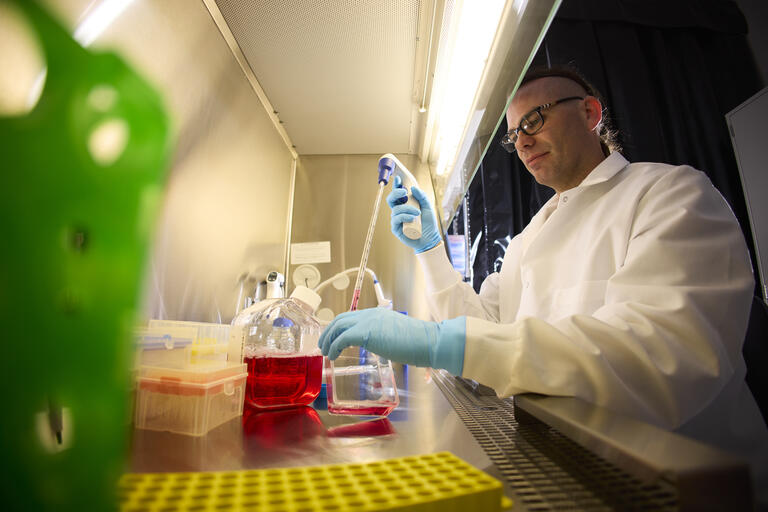

Initially, Wade was tasked with those aforementioned grunt-work duties of cleaning glassware and grinding frozen fish samples. Before long, though, he moved to a data audit group, where he learned the EPA’s environmental analytical methodologies and quality assurance requirements.

Along the way, Wade worked under EPA scientists who were charged with reviewing environmental data from Superfund cleanup sites (places throughout the country that were designated as having high levels of hazardous material contamination that required long-term cleanup).

This work sparked Wade’s interest in pursuing a career in environmental science, which led to his decision to major in chemistry.

“By the time I graduated from UNLV, I had done everything from conducting audits of EPA-contracted environmental laboratories throughout the nation to conducting environmental research on a $500,000 gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer,” Wade says.

With that, Wade was off and running on a lengthy career dedicated to addressing and mitigating environmental challenges in both the private and public sectors.

One of his early career highlights: serving as vice president of a firm that developed one of Nevada’s first private environmental analytical laboratories.

From there, Wade shifted gears back to the federal government, where over the course of more than 30 years he held various staff, management, and senior leadership positions with the DOE. His work spanned everything from environmental compliance and cleanup to nuclear waste and spent nuclear fuel disposition.

Just how important were Wade’s latter-career responsibilities? Here’s the condensed answer:

He provided national-level briefings on nuclear waste programs at locations throughout the United States; he routinely interacted with and briefed Nevada’s elected political officials at the local, state and federal levels (as well as Native American tribal leaders); and he managed diverse federal and support staff on matters related to the environment, health and safety, engineering, construction, drilling, and operations.

Oh, and Wade also managed numerous massive federal projects (each in excess of $1.5 billion), as well as several major federal programs with annual budgets exceeding $100 million.

By now you’re probably thinking, “Well, gee — doesn’t sound like he had much time for extracurricular activities, let alone community service.” And you’d be right.

Yet during his career, Wade somehow found that time.

He authored two novels (a third is on the way); earned a first-degree black belt and became a karate instructor; and served four years as a citizen member of the Clark County Commission’s Air Pollution Control Hearing Board.

All this while raising two sons with his wife Stacy, whom he met just before he graduated from UNLV. (“We still disagree as to who picked up whom when we first met,” he says.)

Since deciding to call it a career in 2022, Wade has kept busy by expanding his community involvement. For instance, he’s been on the Atomic Museum’s Board of Trustees since retiring and served in multiple leadership positions with the museum, including as vice chairman of the board and chair of the Educational Committee.

He also has been a guest speaker on nuclear science at various community events, and talked to Clark County School District middle school students about the creative writing process during Nevada Reading Week.

Not to be forgotten, Wade also has been giving back to his alma mater in significant ways. In 2022, he was appointed to the College of Science’s Board of Advisors, through which he also coordinates with other colleges (including Education, Engineering, and Fine Arts).

Additionally, Wade was invited last year to speak to the Honors College about nuclear weapons, environmental cleanup, and nuclear waste management.

And most personally, Wade has continued to support the Terry Wade Scholarship. Named in honor of his older brother who is disabled, the scholarship supports UNLV students with disabilities or learning challenges.

This ongoing service to UNLV stems from Wade’s deep sense of gratitude for a place where he found his life’s passion (not to mention his life partner).

“Through attending UNLV, I was exposed to so many diverse topics, educational experiences, and activities,” he says. “This diversity of opportunity even allowed me to perform on the UNLV Judy Bayley Theatre stage in 1981 as part of The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial cast. More importantly, it helped me develop on-campus connections and make lifelong friends, including with my brothers in the Sigma Nu fraternity.

“I’m also deeply appreciative of my many UNLV professors who were always knowledgeable, supportive, and kind. My time at UNLV truly helped shape both my career and life arc.”

When did you know for certain that you made the right decision to become a Rebel?

UNLV always felt right, but it was probably during my sophomore year when everything clicked. While taking predominately introductory classes in the physical sciences, I was able to get an on-campus job working for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in their student program. Both that job and my UNLV science education convinced me that I was in the right place.

Your professional career spanned more than three decades, much of it spent working for the U.S. federal government on environmental and nuclear waste matters. Was it always part of your grand career plan to land a federal job in this field?

Not at all. But my environmental chemistry experience with the EPA led to working on environmental compliance — the laws and regulations on air, water, hazardous and radiological waste, etc.

Of course, a career is a lifelong learning journey, and along that journey I developed knowledge in diverse disciplines such as safety and health, industrial hygiene, field engineering, and tunneling/drilling.

I would have never guessed as I graduated from UNLV that years later I’d be worried about such topics as silica dust in an underground environment, drill rig safety, or having to defend groundwater flow and transport for radioactive waste.

Of the academic courses you took at UNLV, which one did you lean on most to set you up for early-career success, and how did that course continue to resonate throughout your career?

Organic chemistry. That course, among many things, gave me a foundation in organic structure and nomenclature, which I utilized in diverse activities from chemical analysis to environmental sampling and even to workplace safety. I even kept my organic chemistry textbook readily handy in my office bookcase for many years.

As I talk with the public today on the Manhattan Project and its origin, I often start with a quick overview of atomic structure, which takes me all the way back to my general chemistry courses at UNLV.

Ultimately, the challenge is to communicate openly and effectively on difficult subjects to those in the public who may not have had the benefit of an understanding of chemistry and physics.

Speaking of communicating to the public, you did a lot of that during your career, leading public forums across the U.S. on a wide range of controversial subjects — most notably, nuclear waste. What were those experiences like?

Mostly rewarding but often stressful — particularly when discussing a difficult topic in places where strongly held public perceptions frequently led to push back on scientific facts.

I tried to communicate and listen to other perspectives, but sometimes the conversations devolved into levels that most individuals — thankfully — never have to live through.

For example, I had people approach me during some of these public meetings and — because of the controversial nuclear waste programs I was involved with — tell me with complete sincerity that they hoped my children got cancer. That was difficult to take.

But as a senior leader in the Department of Energy, I could only nod and move on to talk with another person. Thankfully, the rewarding times talking with the public far exceeded those stressful ones.

What is the general public’s biggest misconception about nuclear energy and/or the nuclear industry?

When people think about the nuclear industry, they often focus on the atomic bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki [during World War II], or the major nuclear power plant accidents such as Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, Chernobyl in Russia, or Fukushima Daiichi in Japan. As a result, people generally are unaware of the immense safety protocols that are in place at nuclear power plant operations.

Other than Chernobyl, no nuclear plant worker or member of the public has ever died from exposure to radiation resulting from an incident at an operating nuclear power plant.

In this country, there are 94 nuclear reactors operating in 28 states, and the operation and safety of these reactors is extremely strong — particularly when compared with other high-hazard industries.

The nearest nuclear reactor to Las Vegas is the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant near Phoenix. However, most people don’t think of its relative proximity or the fact that it’s one of the largest electric power producers in the United States.

Nuclear energy today supplies about 20% of the electric power demand, and that energy is clean and does not contribute to hydrocarbon emissions.

At the Atomic Museum in Las Vegas, we’ve recently installed educational displays about nuclear power plants for a couple of reasons: additional nuclear power plants likely will need to be constructed in the coming years, and the existing ones will continue to operate for the foreseeable future to meet the nation’s increasing energy needs.

The nuclear industry is also needed for such things as radioactive isotopes for medical treatment, new cutting edge medical treatments such as gamma knife surgery, and radioactive medical imaging from X-rays to CT scans.

All of these are positive benefits from the decades of research that followed the first fission reaction. And all of this needs to be better communicated to the public, so they’re informed not only about the risks but also the benefits of nuclear science.

Early in your career, you got involved in karate, eventually earning a black belt and becoming a karate instructor. You also are an accomplished writer, having authored two novels about a decade ago. How did these pursuits enter the picture, and what was the appeal of both?

During my career, it was often challenging to find time for any activity. But after watching my oldest son take karate in the 1990s, I decided to try an adult karate class myself. It was tough walking out onto the mat that first time in my bright white karate gee, complete with white belt. However, I stuck with it for many years, ultimately getting to my first-degree black belt.

I also really enjoyed being an assistant instructor working with new students, both adults and kids, and the personal discipline you had to develop through karate training.

As for writing, I started handwriting my first novel while riding on the bus to my job at the Nevada Test Site in the early 1990s. I found that version years later and it was pretty horrible. However, in the late 2000s, I forced myself to write again. By that point, I’d written many thousands of pages of reports, analyses, contracts, etc., as part of my job. Of course, none of that was creative writing.

By forcing myself to write creatively again, I learned to explore new ideas and how to write in a different structure and content.

Like all new writers, as I completed drafts of novels, I would attempt to get a publisher — and as such, I amassed a sizable stack of rejection letters. Finally, I found a publisher, and my novel Midland was published in 2013, followed by Bloodline in 2015. I have the sequel to Midland half-written, as well as two other novels under development.

I love creative writing and plan to continue. But even in retirement, the challenge remains to find the time to do things, whether it be karate, writing, or volunteering.

A recent UNLV graduate who is hoping to enjoy a long, successful career in environmental sciences asks you for one “must do” and one “must don’t.” What’s your response?

I feel very strongly about the one “must”: A person should be willing and eager to continue their education throughout a career. This can include formal classes and training, on-the-job training, or simply personal enrichment. Even a seniors group I spoke to last year shared with me that it was their priority to have monthly educational topics for their group as part of continued individual growth.

As for a “must don’t,” I’d encourage individuals not to be opposed to taking on new challenges — even if those challenges are outside of your comfort zone. Taking on new challenges forces an individual to grow.

One other “don’t” to consider: Don’t ever forget the people who have helped you along the way, including your family, friends, mentors, and coworkers. Among the many people in my life, I am forever indebted to my wife Stacy and my sons Travis and Justin for their love and endless support.