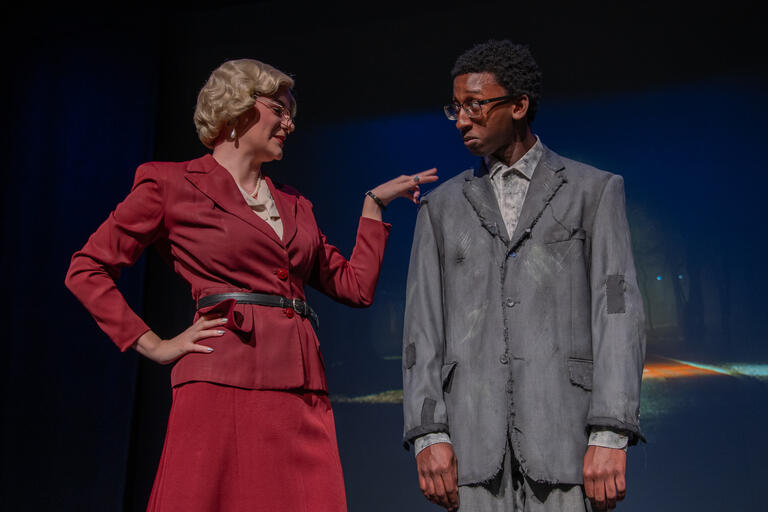

In this uncompromising drama about a people living in bleak poverty, a hopeful young woman is determined to overcome insurmountable circumstances. Stefano “Stebos” Boselli, assistant professor of theatre history and dramaturgy, chats with director Norma Saldivar about this powerful work. Three performances remain: 3 p.m. on Friday, March 29; 7:30 p.m. on Saturday, March 30; and 2 p.m. on Sunday, March 31.

Stebos: Hello Norma, I’m happy to see that you returned to directing after your busy days as Chair of the Theatre Department at UNLV. You told me earlier that Maria Irene Fornés (1930-2018), the Cuban-American author of Mud (1983), directed her play at a theatre where you worked in Chicago. Could you talk about what you were doing at the time and why you got in touch with her?

Saldivar: Back in my post-university days, I was working for a collective. As director of new works, my many duties included developing relationships with playwrights. Actually, Fornés was someone the members of the company had admired greatly, and I reached out to her specifically to do a workshop for the local Chicago playwrights. It was a huge push to inspire and cultivate local playwrights who had been nurtured by Chicago Dramatists, a company that was very friendly to directors and playwrights. Fornés came in and held a week-long workshop that was astounding. She was passionate and shared her passion with not only the participants but the company as well.

Stebos: Speaking about Mud, although its dialogue is fairly realistic, the simple and evocative set Fornés describes in her stage directions recalls one of Samuel Beckett’s — an early influence on the playwright — and the play overall suggests symbolic undertones: can you speak about symbolic elements you chose to emphasize in your staging?

Saldivar: Nothing about the play is realistic, in my opinion. The language is specific and the situation draws on the human experience, but the play is full of symbolism and elevated storytelling. I have tried to honor Fornés’ writing and her thoughts on her aim for the production of Mud, but I also had to really find my own point of view on each of the play’s moments. It has been a constant dialogue and communication with the playwright while pushing the piece to the furthest moments for the audience.

Stebos: The play foregrounds how limitations and accidents may impede growth but also opens up the possibility of hope: how did you approach this tension between what obstructs us and what could allow us to (re)build or even escape, between disadvantages and aspirations?

Saldivar: We try to honor the author’s impulse to just let them exist next to each other. At any moment something seems to be wonderful and full of potential. At the next moment, it turns very wrong. How do we usually deal with this? Do we curse the heavens, or do we just try to keep going? I think this play really explores those tensions. However, it feels a bit like a view of life that we chose to ignore because we don’t feel comfortable with viewing what we might see as unfairness. There is no easy answer in Fornés’ play, just a littering of hope that we have to hold on to. I think that, despite what some may say, this is a hopeful play.

Stebos: In an interview with Ed Wilson, Fornés admitted that the protagonists of her plays were often women, and in that sense that was her “supreme feminist statement”; however, she also argued that she was writing about a person, or humanity in general. How did you read the relationship between sexes in the play? How is power employed, how does it shift as the play progresses?

Saldivar: There is no doubt that there is gender imbalance in this play. No doubt. However, the gender of the characters doesn’t mean anything when we see the choices they make. They are flawed people who have come together to somehow move forward in life, and they don’t always make the right choices. This is not something that unique to a particular gender — it is tragic when it devolves to violence. However, Fornés doesn’t discriminate in the play. The person who wants to transcend their situation does so because of the desire to pursue intellectual desires.

Stebos: In the same interview with Ed Wilson, the playwright remarks that her depiction of violence is a reflection of what she saw in the world, and she is quite explicit in her writing in terms of sexuality, degradation, and violence: what were the challenges in the rehearsal room to finding the appropriate level for these interactions between the actors and the audience’s comfort level?

Saldivar: This is a very interesting question. She pulls no punches. Most everything that is violent happens in front of the audience. We tried to find the root of the action intellectually and mapped out the actual violence with the help of professor Sean Boyd, who was assigned to the stage combat and stage intimacy work. He brought his own point of view but was also extremely respectful of my aims that were expressed in the staging around the violence/intimacy, and open to discussion on the characters’ goals. There was little to no censoring of staging, and I believe we accomplished what she requested in the script. On another side of your question, we kept a very light room. We were able to keep in high spirits and genuinely appreciated every opportunity to work the play. It was a joy to work with the actors and rehearsal hall staff.

Stebos: The ability to learn and improve is a strong theme for Mae, who wants to learn, aims for some sort of “enlightenment,” and falls in love with Henry’s brain, basically just because he can read. What is the role of education in self-improvement that can be gleaned from the play, in your interpretation?

Saldivar: I believe that there is a love of intellectual pursuits in Mud. There is a curiosity that can only be addressed through study and exploration of the world. This exists in Mae but not in Lloyd. Although it exists in Henry, he remains limited in what he will allow to explore. Mae is an observer. She is a critical thinker. She is sensitive to shifts of energy. I believe that the play explores the tensions between education and the negative assumptions of elitism.

Stebos: The play mentions animals with their connotations: pig, starfish, and hermit crab. Was the animal world an inspiration for your work with the performers?

Saldivar: As the characters are farmers and they farm pigs, I researched pig farms and slaughterhouses. This seemed to provide interesting images of containment and almost surreal space.

Stebos: Each of the play’s 17 scenes ends with an eight-second freeze, a still photograph: How did you stage these freezes and what purpose do you think they serve/how are they useful to the characters, actors, or the audience?

Saldivar: The audience will have to see the play to find out. That is definitely a choice.