For many people, the sex industry evokes images of predatory capitalists and creepy guys in trench coats, adult shops with XXX-rated imagery, and cheaply made products. These stereotypes suggest a commercial world inherently inhospitable to women — think seedy back alleys and peep shows. Over the past 40 years, however, the sexual marketplace has undergone a slow and steady transformation, with women leading the way through stylish retail boutiques and socially conscious entrepreneurship.

The women’s market for sex toys and pornography was, until fairly recently, regarded as a relatively small and inconsequential part of an industry far more focused on men. Due in part to the popularity of television shows like Sex and the City—which introduced millions of viewers to the Rabbit vibrator—and the runaway success of Fifty Shades of Grey, women have acquired newfound economic and cultural cachet as sexual entrepreneurs and consumers. Although accurate sales figures are difficult to pinpoint—adult companies keep their numbers extremely close to the vest and virtually no reliable data exist—the women's market for sex toys has become big business in an industry that reportedly grosses upward of $15 billion annually.

These changes did not happen overnight. As I detail in my new book, Vibrator Nation: How Feminist Sex-Toy Stores Changed the Business of Pleasure, understanding the sex-toy revolution, including what the future might hold, requires revisiting the 1970s and the pioneering efforts of feminist entrepreneurs.

Challenging the Patriarchy

By the start of the 1970s, second-wave U.S. feminists, aided by the sexual revolution and the gay and lesbian liberation movement, were dramatically reshaping cultural understandings of gender and sexuality. They challenged the patriarchal status quo that had taught women to see sex as an obligation rather than something they were entitled to pursue for the sake of their own pleasure. They wrote essays about the politics of the female orgasm, attended sexual consciousness-raising groups, and positioned masturbation as a decidedly feminist act. In the process, they recast vibrators as essential tools of women’s liberation.

There was only one problem: In the early 1970s there were few places for the average woman to comfortably buy vibrators, or even talk openly about sex. Conventional adult stores were not designed with female shoppers in mind. Reputable mail-order businesses that sold so-called marital aids were few and far between. And women walking into a department store — or any store, really — to buy a vibrating massager risked encountering a male clerk who might say, “Boy, you must really need it bad, sweetie pie.”

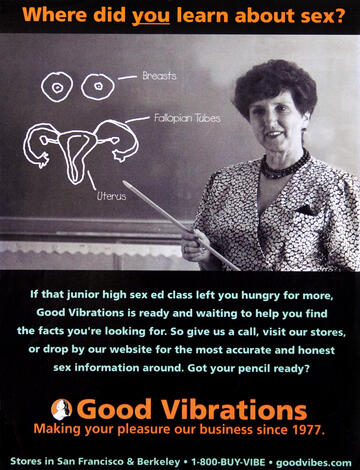

Women’s forays into the sexual marketplace, as both entrepreneurs and consumers, took place against this backdrop. In 1974, Dell Williams founded Eve’s Garden in New York City, the first business is the United States exclusively devoted to women’s sexual pleasure and health. Several years later, Joani Blank, a sex therapist with a master’s degree in public health, opened the small yet charming Good Vibrations retail store in San Francisco. These women boldly reimagined who sex shops were for and what kinds of spaces they could be at a time when no business model for women-friendly vibrator shops existed. (For more on the topic, read "Susie Bright, Good Vibrations and the Politics of Sexual Representation.")

What made these early feminist vibrator businesses so revolutionary, and what set them apart from their more conventional counterparts geared toward men, wasn’t just their focus on women, but their entire way of doing business. They led with sex education not titillation and advanced a social mission that included putting a vibrator on the bedside table of every woman, everywhere. They believed that access to accurate sexual information and quality products had the potential to make everyone’s lives better. They saw themselves, very earnestly, as educators and activists rather than traditional capitalists, and took pride in thumbing their noses at the idea of business as usual in an industry that had long catered almost exclusively to men.

Today, a growing network of feminist-identified sex-toy shops exist in cities across the country, from Seattle to New York, Albuquerque to Chicago, and Milwaukee to Boston. These businesses have adopted elements of the educationally oriented and quasi-therapeutic approach to selling sex toys and talking about sex pioneered by Good Vibrations.

In doing so, they have placed new demands on the larger sexual marketplace. Sex-toy packaging with sultry images of porn performers has been replaced by softer and more sanitized imagery; messages about sexual health and education are regularly used as marketing platforms; and new breeds of sex-toy manufacturers founded by art school grads and mechanical engineers are bringing sleek design, quality manufacturing, and lifestyle branding to an industry that historically has not been known for these things. References to sex toys abound in women’s and men’s lifestyle magazines, and it’s now possible to buy a vibrator at many neighborhood Walgreens.

Feminist businesses have played a major role in making sex toys more respectable, and thus more acceptable, to segments of Middle America that previously would never have dreamed of stepping into an adult store. In the process, they have helped grow a robust consumer niche.

Las Vegas is a city known for risk-taking, innovation, and entrepreneurship. It’s not surprising, then, that these same virtues are enshrined in UNLV’s mission to promote cutting-edge research that investigates emerging economic, cultural, and social trends. In this case, that includes trends in the adult industry, a highly profitable and diverse segment of popular culture that scholars and policymakers know surprisingly little about.

History shows us that women will continue to redefine the sex industry, blurring the boundaries in the process between feminist politics and marketplace culture, activism and commerce, and social change and profitability. Indeed, the story of feminist sex-toy businesses in the United States is one marked by invention, intervention, and, importantly, an entrepreneurial spirit defined by a desire to leave a lasting contribution—much like the story of UNLV.

Lynn Comella, a professor of gender and sexuality studies, is an expert on the adult entertainment industry. She is the author of Vibrator Nation: How Feminist Sex-Toy Stores Changed the Business of Pleasure and co-editor of New Views on Pornography: Sexuality, Politics, and the Law. She was the recipient of the 2015 Nevada Regents’ Rising Researcher Award in recognition of early-career accomplishments and is a frequent media commentator.